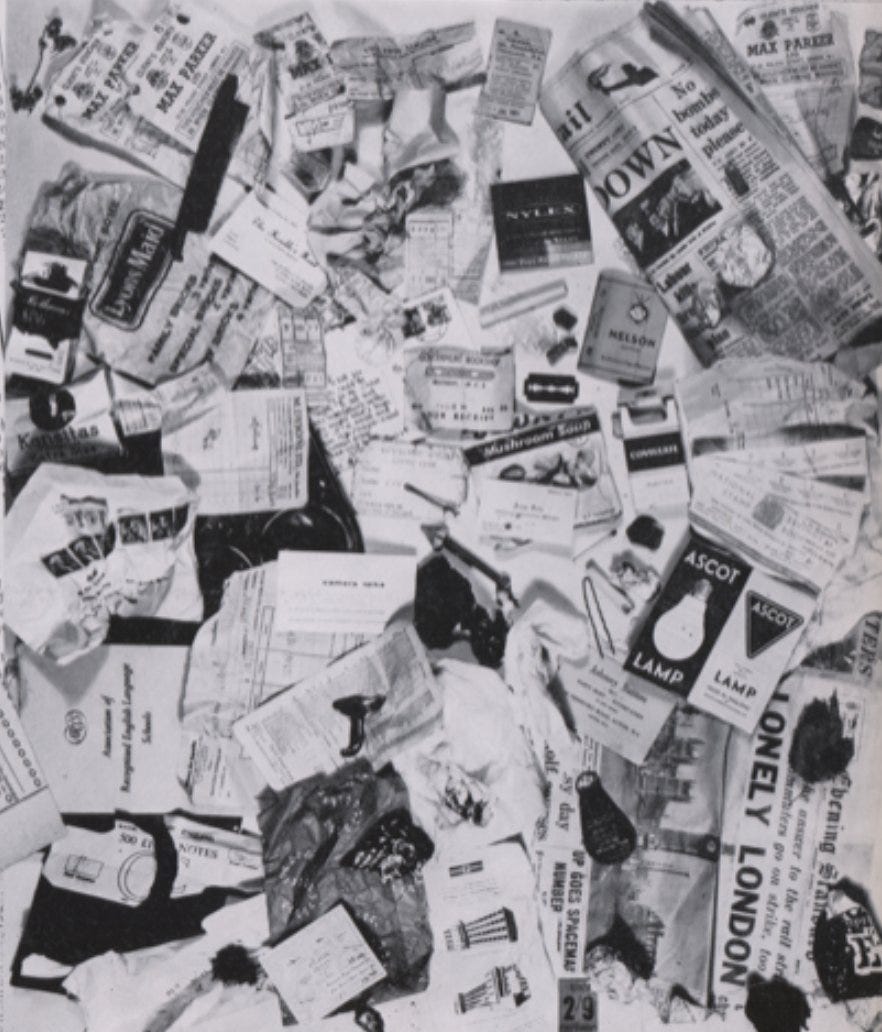

On 3 October 1962, the artist Robin Page performed a ‘Happening’ – a live art event – which involved him standing on London’s Oxford Street asking passers-by to give him ‘anything on their person which they did not value’. He was there from 12:15 in the afternoon until 9:29 at night, which means that the performance coincided exactly with NASA’s Mercury-Atlas 8 space mission, at that point the longest manned mission the agency had undertaken. Page’s ‘simultaneous document’ of the space flight, then, is a kind of jamming of perspectives, wilfully turning away from spacemen and rocketships to ask people in the street what they’ve got in their pockets. Ten years later, Georges Perec would coin the term infra-ordinary as the opposite to extraordinary, and I think this is what Page is playfully getting at with his stunt. Here’s Perec:

The daily newspapers talk of everything except the daily. The papers annoy me , they teach me nothing. What they recount doesn’t concern me, doesn’t ask me questions and doesn’t answer the questions I ask or would like to ask. … How should we take account of, question, describe what happens every day and recurs everyday: the banal, the quotidian, the obvious, the common, the ordinary, the infra-ordinary?

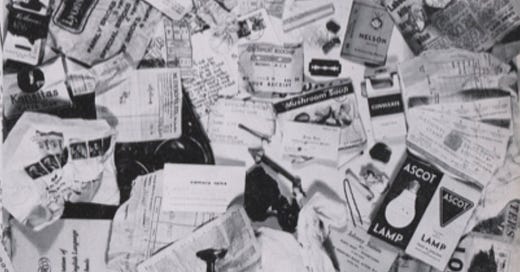

By the end of the day Page had amassed a pile that included envelopes, tickets, flyers, newspapers, matchbooks and pools coupons, electricity bills and bus timetables. It’s a fascinating record of what people were reading – really reading – in that specific moment, the twilight of the post-war era, two days before the Beatles’ released their first single.

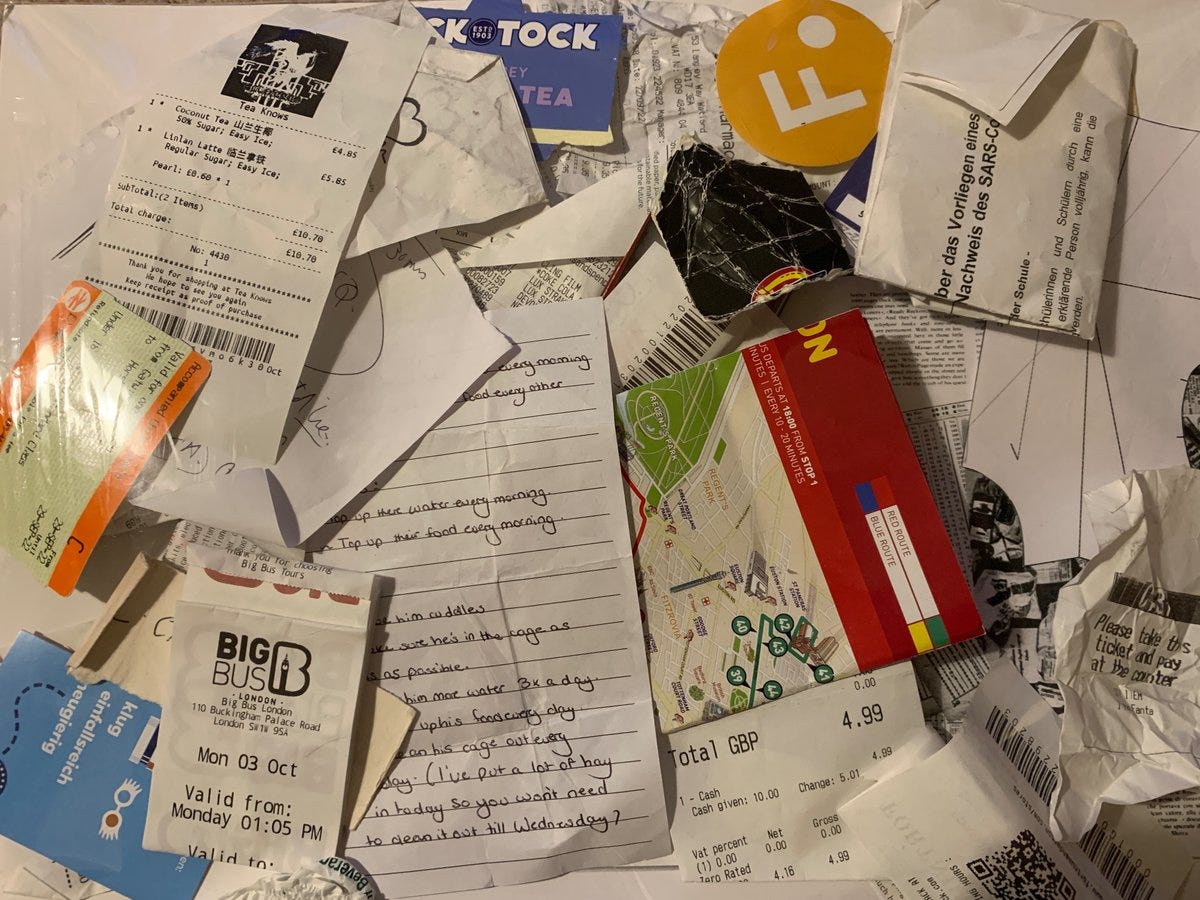

But what, I wondered, would the same experiment throw up if one tried it now? So, a little while ago – 3 October 2022, to be precise, sixty years after Page’s original performance – I spent the afternoon on Oxford Street, snagging passers-by: ‘What have you got in your pockets that you can give me?’

I think if Page had been around today he would have been struck by the number of people who had nothing on them, or at least nothing made of paper. Just a phone and a credit card. This is a story in itself: the dematerialisation of ephemera, the march of information away from slips of paper and into the Cloud. But I was also surprised by the variety of what people did have. Some of it was personal or idiosyncratic: shopping lists, a scribbled recommendation for a TV show. Most of it, however, belonged to the usual categories of pocket ephemera: tickets, business cards, and receipts, receipts, receipts.

It’s an interesting experiment, particularly in terms of setting it alongside Page’s first run of the exercise. But at a couple of years’ distance, I see how there’s a different question, harder to ask, that this exercise doesn’t address: what have you got in your pockets that you won’t give me? The disposable papers that we choose not to dispose of. The ephemera that we form attachments to, things we carry around in our wallets and bags – secretly? semi-secretly? – because they have become meaningful to us. The ticket stub from that gig, the doodle or note from a child or a loved one.

One man who stopped for me on Oxford Street gave me a sheet of notepaper with written instructions on how to feed a duck. Handing it over, he explained that one of his children had stolen an egg which had subsequently hatched. As a punishment/teaching moment, he had insisted that the child therefore be responsible for the duckling’s upbringing. Now the child was going away on a school trip, and they had written instructions for what needed to be done in their absence: top up their food and water, change the hay, ‘give it cuddles’. Don’t worry, he told me, he had memorised it by now. Just a piece of paper that wasn’t needed any more, then. Still, I’m surprised that he gave it so easily, handing it over to a stranger in the street just because I asked.

Does the handing over and photographing of the infra-ordinary elevate something to extraordinary? Can the infra-ordinary ever be seen? Or can it only ever be presumed, alluded to, glimpsed maybe, but not noticed? What do quantum physicists have in their pockets?

What a fascinating experiment! I still write shopping lists on scraps of paper so I’d probably have had one of those in my pockets if you’d asked!